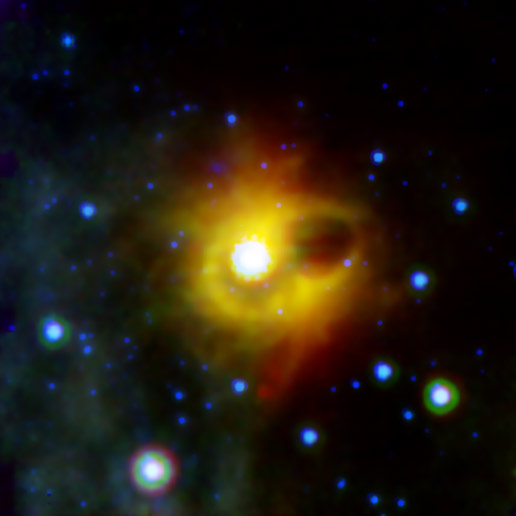

Magnetars are apparent neutron stars with incredibly strong magnetic fields. Their magnetic fields are hundreds or thousands of times stronger than those even of pulsars, which are rotating neutron stars that have extremely strong magnetic fields themselves. The incredibly strong magnetic fields of magnetars powers beams of X-rays and gamma-rays, which make the radio beams of pulsars seem weak in comparison.

Quark stars, on the other hand, are heavy balls of ordinary matter where even neutron degeneracy pressure is not enough to keep them neutron stars. With the enormous pressures, neutrons break apart into their constituent quarks to form a quark star. Unlike neutron stars, the existence of quark stars is not as firmly established, although the evidence for their existence both through observations and theoretical models seems to get stronger all the time.

Computer simulations by Canadian researchers suggest that the best explanation for magnetars is that they may in fact be quark stars. Their simulations show that in a quark star, the quarks pair up to form Cooper pairs as they go into a color-flavor locked phase, which can give rise to color ferromagnetism and generate a tremendously powerful magnetic field. Cooper pairs are the basis for superconductivity and superfluidity in ultra-cold metals and helium, and likewise the color-flavor locked quarks form a superfluid inside the quark star.

The core of at least some neutron stars also probably form a superfluid, as one of the properties of a superfluid is that it can only rotate at discrete speeds, which shows up as “glitches” in the period of a pulsar. What blows my mind is the formation of superfluids in neutron stars and quark stars: it boggles the mind to think of matter flowing with absolutely no resistance at all under high pressures that are beyond imagination. And it might be responsible for the high magnetic fields of a magnetar.

The computer simulations also suggest that it might take days to thousands of years for a heavy enough neutron star to turn into a quark star after a supernova, presumably after the thermal activity of the neutrons cool off so that the heat would no longer help prop up the neutron star. And given that less than 5% of the mass of a neutron is due to its constituent quarks, with the rest from the binding energy between the quarks and their kinetic energy, the transition from a neutron star to a quark star should release humongous amounts of energy as a significant portion of the neutron star’s mass turns into pure energy. It might even dwarf the energy released in a supernova.

This is another thing to boggle the mind: something only tens of kilometers across could release energy comparable or even larger than what a star millions of kilometers across could release as it implodes during a supernova.